In detail, for those interested!

Early agricultural civilizations

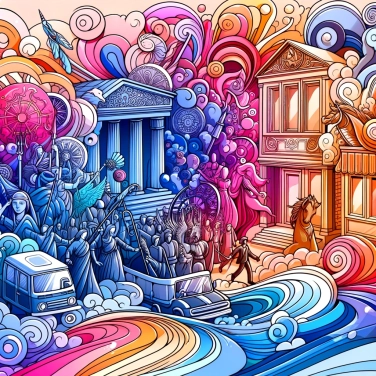

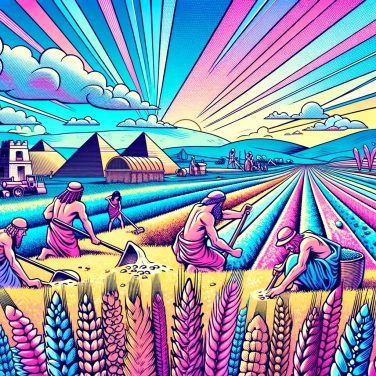

The first agricultural civilizations appeared about 10,000 years ago, marking a major turning point in human history. The first known examples of such societies were found in the Middle East, in Mesopotamia and in Egypt, where the first forms of agriculture were developed. These civilizations emerged along fertile rivers, such as the Tigris, Euphrates, and Nile, which provided the necessary water for crop irrigation. Agriculture allowed these societies to settle down, develop more complex social structures, and partially break free from dependence on hunting and gathering for their food.

Dietary need

The first civilizations cultivated cereals in abundance primarily to meet their growing food needs. Cereals such as wheat, barley, rice, and corn were sources of essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, proteins, fibers, vitamins, and minerals necessary for the survival and health of ancient populations. The cultivation of cereals provided a stable and reliable basis for food, allowing more and more people to be fed and supporting the population growth of early civilizations. By ensuring a constant food supply, cereal cultivation allowed ancient societies to thrive and develop, freeing up time and resources otherwise devoted to food gathering. Surpluses of cereal crops also enabled the development of trade, craftsmanship, art, and other cultural and economic activities within these civilizations.

Impact on the development of societies

The first agricultural civilizations saw the emergence of more complex and sophisticated societies. The intensive cultivation of cereals allowed to feed larger populations, which led to the growth of cities and the development of dense urban centers. The availability of abundant food also freed up time for other activities than hunting and gathering, facilitating the emergence of specialized trades and the division of labor.

The sedentarization of agricultural populations favored the establishment of more organized political and social structures, with the emergence of distinct social classes, centralized governments, and legal systems. The food surpluses generated by cereal cultivation allowed for the development of trade, exchanges, and interactions between communities, thus promoting cultural and technological exchanges.

Cereal farming also had an impact on the environment, with the transformation of land to make it cultivable and the development of sophisticated irrigation systems. These developments contributed to the modification of landscapes and ecosystems, marking the beginning of the human footprint on the planet.

In short, intensive cereal cultivation deeply transformed human societies by promoting the rise of complex civilizations and paving the way for more sophisticated forms of social, political, and economic organization.

Benefits of growing cereals

Cultivating grains has many advantages for early agricultural civilizations. First of all, grains are plants rich in carbohydrates, making them an essential source of energy for humans. By cultivating grains abundantly, ancient societies could ensure a regular food supply for their population.

Furthermore, grains are relatively easy to cultivate and store. Wheat, rice, corn, and other grains can be stored for long periods, allowing ancient civilizations to build up food reserves to cope with times of famine or poor harvests.

Grain cultivation also allowed for the development of more complex societies. By producing a surplus of food, early agricultural civilizations were able to free up part of their population from agriculture to focus on other activities such as craftsmanship, trade, or governance.

Lastly, grains played a crucial role in the development of agriculture and animal husbandry. Grain crop residues could be used as feed for livestock, contributing to the breeding of larger herds. Additionally, grain agriculture promoted the sedentarization of populations, marking the beginning of more complex and organized societies.

![Explain why some countries change time zones?]()

![Explain why Alexander the Great refused to wear shoes.]()

![Explain why Alexander the Great always wore an impressive helmet.]()

![Explain why the last Chinese emperor was so young when he came to power?]()